Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem speaks of a powerful ruler who’s works the sands of time have buried. All that remains is a stump of a statue and the scrawled inscription:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings: Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!

In our day that ruler is God. On the Greyhound where God was once seen as pre-eminent, he has now been pushed to the back of the bus. And the key to this coach is omnipotence.

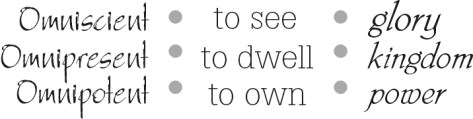

We are taught that God has three major characteristics, which are:

- Omniscience – God sees/knows all

- Omnipresence – God is everywhere

- Omnipotence – God is all powerful

Notice, though, that the first two, omniscience and omnipresence, are regarded as immutable. God does not choose to see all. God does not choose to be everywhere. Because of who he is, these characteristics just are. But when the talk comes to omnipotence, suddenly it is part of some feature set. Like air conditioning, it is turned on and off at a whim.

How many times have you heard someone say, “God could have (fill in the blank), but he chose not too?” Then comes the long list of possible explanations as to why he did not do said thing. The problem is, as time goes on the works of God become buried under the sand of potentials.

In When Prophecy Fails, Leon Festinger examines how a failing prophecy can actually make a group of believers grow. It is this kind of cognitive dissonance that creeps in under the guise of faith, knitting the true believers closer together, while causing the onlookers to become more and more incredulous.

At the root of much of this in Christianity lies omnipotence. If God could do anything — from a human point of view — the works of God would become random acts (a point we will examine at a later date), therefore omnipotence cannot be the ability to merely do anything you want. And it is not.

Omnipotence is the hand of God upon his creation. It is said of Christ that in him and through him all things consist, cohere and are held together. This is omnipotence. Every act around us happens in the omnipotence of God. God doesn’t choose to be omnipotent, he just is.

Naturally, this returns back to pattern. So, for a little background, let us delve into mining. Let us suppose you are wandering around Yukon with the desire to put a little bit of gold dust into your pouch. The first thing you would do is find an area you thought was promising. You would pound in your boundary markers, you would stake a claim. Next, you are required to prove your claim. You can’t just grab land indiscriminately; you have to put in some labour. Finally, after labouring, you have control over that claim.

In pattern, this example plays out as follows:

- Omniscience – stake a claim

- Omnipresence – prove a claim

- Omnipotence – control a claim

As a biblical example, let’s take a look at the relationship between Babylon (the Chaldaean empire) and Judah.

Omniscience – stake a claim

There was nothing of value in all of Judah that King Hezekiah did not show the envoys from Babylon. Isaiah 39:2

Omnipresence – prove a claim

King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon is making war against Judah. Jeremiah 21:2

Omnipotence – control a claim

Nebuchadnezzar took the people as captives, and carried away the gold, silver and bronze from the temple of God. Jeremiah 52

As this example shows, to see is to stake a claim. That is why it is said that God cannot look upon sin, for he has no claim upon sin. To labour, to suffer, to make war is to prove a claim. This is habitation, which is to be present and working. Finally, ownership is shown in the reward of labour, in the control of that thing laboured over. This plays out as follows:

In this you may breathe, what is for you, the first breath of pattern. So we will carry this forward just a bit farther.

When Christ declares that the kingdom, the power and the glory are God’s, one thing that is occurring is a reaffirmation of the omniscient, omnipresent and omnipotent characteristics of God.